DevOps Django - Part 2 - The Pain of Deployment

This article is part of a series I’m writing called DevOps Django. This series is meant to explain how to best deploy modern Django sites. If you’re new, you should probably read the first article of the series before this one.

What I Build

As I mentioned in the first article of the series, I work at a tech startup building telephony services. Our primary product is a hosted teleconferencing platform that hundreds of thousands of callers use each month. As all my experience with deployment has (primarily) come from building and maintaining this platform, I’d like to take this opportunity to explain what I actually build.

Our product is broken up in two primary components: a telephony layer that powers our core teleconferencing service, and a web layer that powers our API back end and user portal. Having two completely separate (and isolated) infrastructures means having to deal with multiple deployment patterns.

Our telephony infrastructure is built on top of:

- Ubuntu server, a great Debian based operating system.

- Asterisk, the open source PBX engine.

- OpenSIPS, the open source SIP router.

- Cisco hardware (for routing physical calls over multiple DS3 circuits).

- NFSd, for storing large amounts of sound files.

The majority of our telephony code is written in Asterisk’s custom scripting language (dial plan). This language lets us completely control call behavior. With it, we can do things like:

- Play sound files.

- Record sounds.

- Bridge multiple calls together.

- Recognize touch tone input and perform other actions.

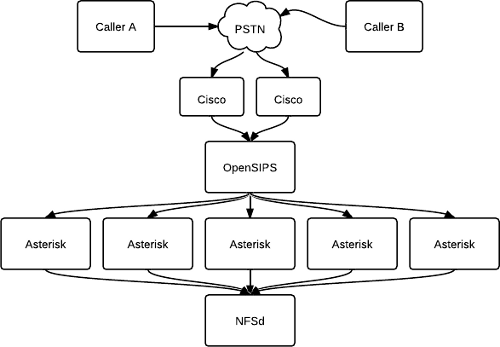

Here’s a small diagram which shows how our physical infrastructure is designed (excuse my poor diagrams, I’m awful with this stuff):

The way things work here is that callers (e.g. you) dial our phone number on your cell phone (or land line, whatever) and your call travels through the PSTN (public telephone network). Your call eventually arrives at our Cisco equipment, which converts the calls from hard line formats into VoIP, so that we can easily move the call around our network.

From there, your call is sent to our load balancer (OpenSIPS), which determines which Asterisk server should handle your call. At this point, your call is then sent to Asterisk, which does whatever needs to be done.

The NFS server is used to store user generated sound files. This way, our Asterisk servers can remain stateless (we can simply plug more Asterisk servers into our network at any time to increase capacity).

Where things get interesting is our web infrastructure. Our web stack provides lots of functionality to our systems, including:

- The ability to manage conference rooms in real time. This includes stuff like muting callers, banning callers, changing caller nick names for easy identification, etc.

- Centralized logging of all user metrics: which conference rooms they use, how often, what features they use the most.

- Billing integration that allows us to track how many minutes are being used by each conference room.

- Account management for users (and administrators).

- An API that our telephony infrastructure uses to communicate with us.

- Other cool features that I won’t get into.

Our web stack was built using the following technologies:

NOTE: I’m choosing to list the old technologies here as this article is focused primarily on my original problems deploying Django. While I’ve solved a majority of my problems, that will be discussed in a future part of this article series.

- Python, our favorite programming language.

- Django, our favorite web framework.

- RabbitMQ, a useful queueing system.

- Celery, a distributed task queue.

- Memcached, a simple caching server.

- FreeRADIUS, an annoying and stupid (but necessary) system for logging call metrics.

- MySQL, an incredibly frustrating database server.

- Git and GitHub, for version control.

And this is a list of our old infrastructure tools (most of these are gone now in our new environment):

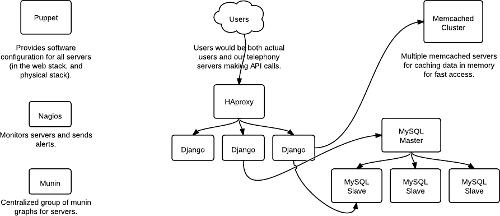

- Puppet, a centralized configuration management service. Essentially, it allows you to write scripts that automatically configure your servers in a modular fashion.

- monit, application monitoring software we used for automatically fixing critical problems and sending alerts. It lets you do stuff like say “send me an alert if the CPU usage on this box goes above 50%”.

- munin, a simple monitoring tool that generates useful graphs (network traffic, CPU usage, etc.).

- nagios, a popular system monitoring tool.

- HAProxy, the fast HTTP load balancer.

- Nginx, our web server of choice for buffering HTTP requests locally to our WSGI server.

- Gunicorn, a unicorn with a gun. OK, not really… It’s actually a pretty awesome pure Python WSGI server.

- Jenkins, a simple continuous integration server for running tests and deploying code to production.

- Rackspace, our server host.

These are the core technologies that we used to develop our web stack over the past two years (up until a few weeks ago).

I’ve taken the liberty of drawing this up in a small diagram (again, excuse my poor diagramming skills):

As you can probably imagine, we use Python and Django to build our website and back end API. These are the core technologies that power our web services. RabbitMQ holds our queued tasks, and Celery processes the queued tasks and executes them on worker servers asynchronously. Memcached is used to store data in memory for fast retrieval (stuff like lists of banned callers, etc.) and MySQL was used to store all of our persistent data.

FreeRADIUS is really in a league of its own, as we use it exclusively to track call metrics from our physical Cisco devices. Most high end Cisco equipment supports radius logging, so we have a FreeRADIUS instance running at all times to track our physical call metrics (which calls enter and leave our network before ever talking to our telephony servers), as this data is far more accurate than data that arrives via API calls (due to timing issues across the network).

In regards to our monitoring software (puppet, etc.) we used quite a mix. The reason being that no one piece covered all our basic requirements. For our services, we wanted to have the following:

- Alerts when stuff goes down.

- The ability to automatically fix weird issues (restart services that stopped, etc.).

- Graphs to show CPU usage, memory usage, etc., so that (as a devops guy) you can scale your infrastructure as necessary, spot bottlenecks, etc.

- The ability to automatically provision new servers. Manually provisioning

servers is:

- A waste of time and energy.

- Error prone (what if you forget to do something?).

- Not scalable.

- The ability to quickly and easily confirm things are working.

A lot of our core functionality comes from the integration between our telephony services (which are co-located at various data centers around the US), and our centralized cloud platform. Due to the dynamic nature of our architecture, our web platform is extremely important. If our web platform goes down, our users see a majority of their features vanish instantly, as we can’t log usage data, perform authentication checks against users, etc.

With both parts of our stack working together, we’re able to give our users a really great experience both through their phone and browser.

Why Deployment was Painful

As our product focuses on real time user communication, we have a lot of technical challenges. Our service needs to:

- Provide fast interaction between our physical telephony infrastructure and cloud infrastructure.

- Provide accurate logging information for billing.

- Maintain high availability for our systems, as even a minute of downtime effects thousands of callers.

- Rapidly push changes to our applications in production with no maintenance windows.

With our intense availability requirements, I’d say that (up until our recent infrastructure change), I was spending about 90% of my time working on either maintaining our infrastructure and tools, updating components, automating components, or scaling our components.

Given the fact that we have so many different technologies (a lot of them requiring their own servers and redundancy), complexity couldn’t be helped– even using modern tools like puppet, monit, nagios, etc.

If you’re into devops type stuff, you might be wondering what problems I had given my setup. After all, a majority of the technologies I was using are quite popular in high-tech circles. People look at you funny if you work at a tech company that doesn’t use puppet (or chef) and nagios. These tools have a reputation for making your life easier (as a developer), and supposedly let you focus more on coding than sysadmin tasks.

Despite the hype, building out your infrastructure and monitoring tools is hard. Really hard. If you want to do it right.

Firstly, let’s talk time. The time required to learn all of the infrastructure technologies we used was immense. As anyone who knows me can attest, I spend a ridiculous amount of time programming. Even with the insane hours I consistently pull hacking code, it took a long time before I was able to build quality puppet modules, monitoring scripts, and deployment tools.

Once we started heavily using our infrastructure tool set: puppet, nagios, monit, etc., I found that I’d spend at least 90% of my time throughout the workday either:

- Writing new monitoring and deployment modules.

- Fixing bugs in old monitoring and deployment modules.

- Dealing with random one-off issues that occur because of slight differences in production environments.

Since my company is small, and engineering time is our most valuable resource, this was a real killer.

Secondly, hosting cost becomes an issue. When you require high availability for your services, you can’t run just one of anything. This led to a ton of overhead cost on Rackspace, as we had at least two of everything running constantly. Ouch. Not to mention the time it took to engineer the backups / restoration / monitoring tools so that they would actually be useful in the event that a service died.

For the longest time I always assumed building fail proof services would be easy. How wrong I was! Even the simplest of services, take RabbitMQ for instance, requires an immense amount of planning, thought, and maintained focus to build properly. In an environment where you rely on that RabbitMQ server being available 24x7 with as many nines of availability as possible, even the simplest of services can become an enormous pain.

Engineering failover that works is an art. A time consuming art.

Third, MySQL. ARG! Ever tried to automate MySQL deployments? I dare you to build a puppet module that can successfully spin up MySQL replication slaves on demand. It is so painful that I’d rather slap myself in the face with a porcupine than attempt that again.

NOTE: I tried endlessly to find (and build) a decent puppet-mysql module.

I found numerous semi-maintained ones on GitHub, but never found a single

working one. The one I ended up building myself (and using) was so tightly

coupled to my specific deployment scenario that I actually still wake up in hot

sweats on occasion just from thinking about it.

MySQL is annoying to manage in production.

Fourth, complexity. Having so many tools deployed just to keep things running is a real pain. Not only is it a time sink, expensive, and hard to maintain– it is complex.

Complexity gets you in subtle ways.

For me, complexity manifested itself in coupling issues. With such a large amount of scripts, tools, and services–making a change anywhere in the code base was likely to break some part of our deployment or monitoring tool set. This was especially annoying, as it diverted a lot of attention that could have been spent better elsewhere.

Painful Lessons

Since I first started building our teleconferencing service almost two full years ago, I’ve learned quite a bit about deploying Django. Before completely overhauling our service and porting everything to Django, I was relatively inexperienced with production deployments, having only built small passion projects.

What I learned through all of my experiences learning (and using) a variety of popular sysadmin and devops type tools is that nothing in the sysadmin (or devops) world is perfect. There are some great tools out there (puppet), but they’ve got a long way to go before they’re simple enough that a single devops guy can build out an entire production infrastructure solo.

By far the greatest hurdle I encountered over the past two years has been infrastructure. There is a huge time investment gap between building a basic infrastructure (installing Nginx, Gunicorn, celery, etc., on a single server), and automatically provisioning that same infrastructure (with puppet, etc.). In regards to the difficulty of actually writing code that can scale across a large infrastructure, the challenges have been much simpler to overcome. In fact, I’m happy to say that using Django has been an excellent choice for us.

Regardless of the difficulties I’ve had over the past two years in building out our infrastructure, and effectively deploying Django–it has been a great learning experience. I’ve learned more these past two years than at any previous point in my life.

But for me, what it really comes down to, is…

I’m a programmer at heart. I like coding and building new things. At the end of the day, it hurts me inside to spend a ton of time working really hard to maintain and scale your infrastructure, and then realize that through all your effort, you’ve only managed to fight off the chaos for another day. Bummer. I’d rather be hacking on new Django modules, or playing around with the latest asynchronous Javascript framework.

But that’s just me.

In the next part of the series, I’ll be discussing the first part of the deployment solution I discovered.

UPDATE: I finished part 3 of the series, you can read it here.

PS: If you read this far, you might want to follow me on Bluesky or GitHub and subscribe via RSS or email below (I'll email you new articles when I publish them).